July is the month when the schools break up, when families depart for summer holidays, and when election analysts can have a well deserved break too – for the most part. In January and February, the world saw eight national elections in each month, seven in March, ten in April and May, and 12 in June. However, July saw the fewest national elections with just six taking place across the globe. So election analysts hoping for a quiet month may still have some work to do.

Key amongst these was the UK’s general election that saw the Labour Party cruise to an expected landslide, winning 411 seats in the House of Commons. The election was viewed as the sharpest rebuke of the Conservative Party in its history as they were left with just 121 seats and just shy of 24.0% of the vote. Aside from these topline figures, there are greatly interesting results that lie beneath the surface.

For example, one eighth (50) of Labour MPs represent super-marginal seats (with majorities of less than 2,000). This is notably higher than previous governing parties have won in recent years. In 2019, 19 of the seats won by the Conservatives fell within this category. Of course, many would say that this wasn’t a proportionate result to Labour’s result in July. However, in 1997 New Labour won just 16 seats from the Conservatives with majorities of less than 2,000. Should the Conservatives pick up these 50 seats, it would do so on just a 2% swing from Labour. It would still place them on just over 170 seats, still a dismal showing, and far from the levers of power.

The results also showed that Reform UK might have more success at the next election should they ‘take the fight to Labour’, as the party’s leader Nigel Farage MP, has vowed to do. For example, of the party’s 12 target seats at the next election, eight are Labour-held with Llanelli (currently represented by Dame Nia Griffith MP) standing just over 750 votes in both directions away from being Reform’s first Welsh seat. Other vulnerable seats include Hornchurch and Upminster, Sittingbourne and Sheppey, Basildon and Billericay, and Norfolk South West – home to the 2024 ‘Portillo moment’ when former Prime Minister Liz Truss lost her seat to Labour’s Terry Jermy.

The Greens quadrupled their representation, winning all their target seats and coming a close second in four further seats – notably Huddersfield, the Isle of Wight’s eastern constituency, and both Bristol East and South. In particularly urban areas, their success largely came from a large protest vote against Labour’s stance on Gaza. Some key surprises from the election came from pro-Palestinian Independent candidates defeating established Labour names such as Kate Hollern and Jonathan Ashworth, and nearly toppling several more. The efforts by both the Worker’s Party of Great Britain (led by George Galloway), and the pro-Palestinian Independents nearly resulted in high-profile casualties including Jess Phillips (who survived by 693 votes), Naz Shah (by 707 votes), Wes Streeting (by 528 votes), and Rushanara Ali (by 1,689 votes). This is part of a broader haemorrhage of the Muslim vote for Labour as it lost more than half a million voters in constituencies home to the highest Muslim populations, reversing its gains during the Corbyn era. Whilst the party retained 17 of the 21 seats where Muslims make up more than 30% of the population, its vote share dropped by 29 percentage points on average.

With Keir Starmer and Labour now in power, like any prime minister they must begin to cultivate and build relationships on the world stage – that requires navigating other elections in other countries, working with the victor to strengthen bilateral ties. However, with the following elections, this may be beyond the scope of possibility – and even reality.

Venezuela’s election produces two presidents

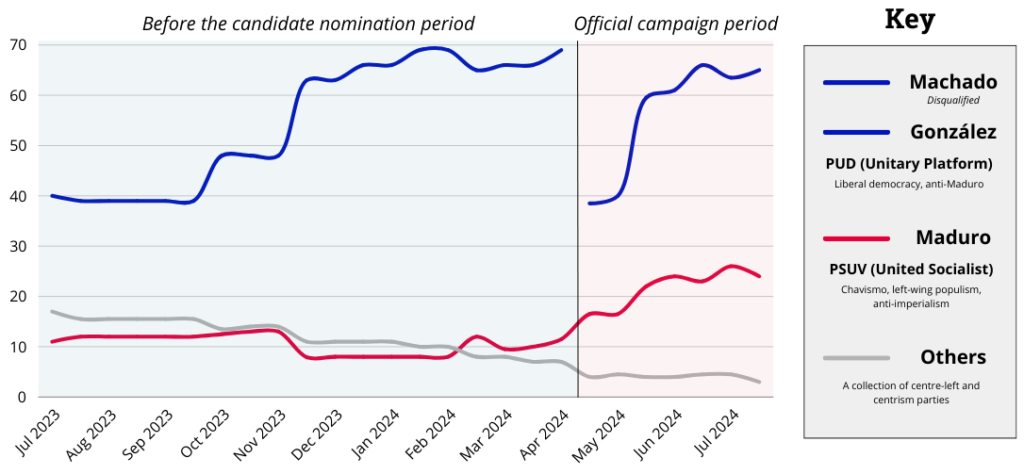

Venezuelan President, Nicolás Maduro, opted to run for a third consecutive term. In his 11th year in office, Maduro was challenged by former diplomat Edmundo González Urrutia at the head of the united opposition movement. The election was fought against a backdrop of an economic crisis owing to a drop in oil prices, corruption, and fiscal mismanagement that has seen millions of Venezuelans emigrate, and social anger at the Maduro regime rise. This sentiment has built considerably since the mid-2010s, but was exacerbated when his United Socialist Party proceeded to ban candidates and parties from standing in the 2018 presidential elections by painting them as ‘out-of-touch elitists in league with foreign powers’.

However, owing to spiralling public opinion against his rule, and a slate of crippling economic sanctions imposed by the USA, Maduro permitted the Unitary Platform opposition to participate in the election – a move that was essentially designed to bolster Maduro’s image and relieve US sanctions. This was successful, but short-lived. Once the regime began to backslide on its commitments to a fairer contest by blocking the candidacy of the Unitary Platform leader and opposition powerhouse María Corina Machado, the sanctions were reimposed.

Machado had emerged as a champion against corruption and economic mismanagement in 2023, rallying millions of Venezuelas to vote for her in the Unitary Platform’s October primary election. Maduro, sensing a threat to his power, declared the primary illegal and opened criminal investigations against some of its organisers. Since then, he has issued arrest warrants for some of Machado’s supporters and staff, whilst the Supreme Tribunal of Justice (a court whose independence has been largely discredited) upheld a decision to remove her from the ballot. However, she kept campaigning and became more of a symbol – a figure behind which Venezuela’s voting population could rally behind.

Machado endorsed González, who commenced a campaign promising an economy that will lure back the millions of Venezuelans that migrated since Maduro became president in 2013. They attracted resistance from Venezuelan police, however González remained on the ballot. Every single public opinion poll conducted before the election showed González winning the election by landslide margins. Additionally, according to an early July poll by Delphos, Maduro’s presidency was viewed as either ‘excellent’ or ‘good’ by 26.5% of the population, whilst 72.3% stated it was ‘bad’ or ‘very bad’. Indeed before the election result was announced a combined total of 56.2% of voters believed the Unitary Platform would win (whilst 20.8% of this figure believed it would win, but Maduro would remain in power).

In a separate poll by ORC Consultores, improving the economy was found to be the most important issue in the mind of voters, whilst improving the health system was next with 9.5%. Breaking down each voter bloc, the poll also found that González led Maduro by significant margins with voters of all age groups, all genders, and all regions in the country. The only somewhat competitive voter group that Maduro still had a small chance to persuade was the +60 age bracket – a group that still preferred González by 48% to Maduro’s 22%.

However despite all of these polls, Venezuela’s electoral authority, blasted by critics as favouring the regime, proclaimed Maduro the winner, saying he won 51% to González’s 46%. Immediately this sparked widespread deadly protests across the country in which over 2,000 people were detained in connection to ‘crimes’ during the protests. Soonafter, the US State Department released its own assessment of the results saying “the processing of those votes and the announcement of results by the Maduro-controlled National Electoral Council (CNE) were deeply flawed, yielding an announced outcome that does not represent the will of the Venezuelan people… it came with no supporting evidence… Meanwhile, the democratic opposition has published more than 80% of the tally sheets received directly from polling stations throughout Venezuela. Those tally sheets indicate that González received the most votes in this election by an insurmountable margin. Independent observers have corroborated these facts.”

According to these tally sheets held by the Unitary Platform, González won the election with around 67% of the vote to Maduro’s 30%, winning every district in the country. Maduro accused the opposition of producing fake evidence to contest the result of the election and said the US was behind what he described as a ‘farce’ and a ‘coup’ attempt. Argentina, the European Union, the G7, Ecuador, Uruguay, Costa Rica, and Peru all recognised González as the new President of Venezuela, whilst the governments of Brazil, Colombia and Mexico called for an ‘impartial verification’ of the result.

Those who acknowledged the CNE’s election results and congratulated Maduro included an assortment of Syria, North Korea, Iran, Russia, Cuba, China, and Vietnam – with Türkiye the only NATO member to recognise the results. With the results still disputed, great social unrest is to be expected in the coming weeks – and this could inspire Maduro to embark on a great crackdown against dissent, employing the military to exercise his will against his own people.

Iran’s ‘reform in name only’?

Since 1979, Iranian politics has largely been divided into camps – principalists, and reformists. The former have dominated the country and are interchangeably known as the Iranian conservatives. Many commentators view this faction as the ‘hardliner’ group who advocate for protecting the ideological ‘principles’ of the Islamic Revolution’s early days. Meanwhile, the reformists were emboldened by Iran’s ‘reform era’, often said to have lasted from 1997 to 2005, and the length of President Mohammad Khatami’s two terms in office. They have been known to advocate for Islamic democracy, liberalism, though also now believe in reconstructing and reconciling their reformism with the more hardline principles of the (now-deceased) Ayatollah Khomeini’s ideas.

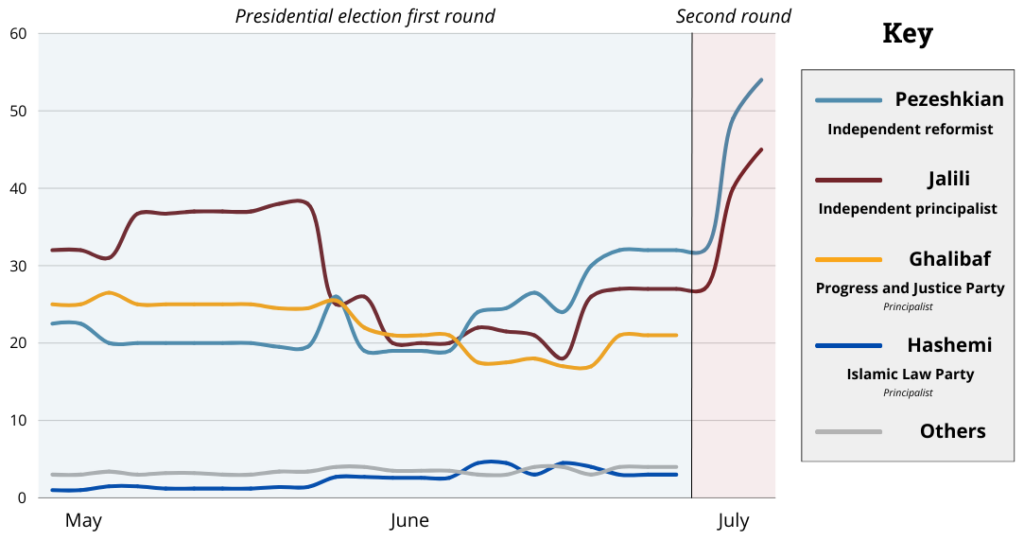

Despite dominating the political landscape for almost 50 years, the principalists suffered an unexpected loss at the hands of reformist Masoud Pezeshkian, reflecting deep dissatisfaction with the direction of the country in recent years and opening potential new avenues of cooperation with the West. Winning 16.3 million votes against ultra-conservative Saeed Jalili’s 13.5 million, Pezeshkian defeated three principalists to succeed the late Ebrahim Raisi, the country’s former President who died in a helicopter crash in May.

Under the slogan ‘For Iran’, Pezeshkian has been an advocate of letting women choose whether to wear the hijab and ending internet restrictions that require the population to use VPN connections to avoid government censorship. He said after his victory: “The difficult path ahead will not be smooth except with your companionship, empathy and trust.” Whilst some regard him as being naive, much of his campaign centred around his own personal integrity. Whilst he has said he is loyal to Iran’s supreme leader, Ayatollah Khamenei, he has also said he will resign if he feels he is being thwarted, and will then call on the population to withdraw from the political process.

What he wants to achieve as President may also mean a thawing in the hostile relationship between Iran and the United States. For example in successive TV debates he said he was unable to bring about change, including the lowering of 40% inflation, unless he could secure the lifting of some sanctions imposed by the international community. He stressed that Iran needed to be more cooperative to see if sanctions could be lifted. His vice presidential running mate, former Foreign Minister Javad Zarif, has experience of rapprochement with the West – he negotiated the nuclear deal in 2015 that led to a lifting of sanctions, before Donald Trump pulled the US out of the plan in 2018.

Pezeshkian’s victory came following the 2021 presidential election in which no reformist was allowed to stand. However, following the ‘women, life, freedom’ protests in 2022 and considerable public uproar against the trajectory of Iranian politics and society, he defied the rule of Iranian politics that reformists lose if turnout is low. It also follows the parliamentary elections earlier this year in which principalists trounced reformists. There were allegations that the conservative establishment sought to rig the results through sudden surges in late votes, and reports that government funds were being used to send clerics into rural villages to solidify support in Jalili heartlands.

Pezeshkian will need to assess how close to the West he wants Iran to get. It might be in his country’s interest to have warmer relations in order to relieve some of the sanctions his country faces, but simultaneously, there is great national unity for continuing to support Hezbollah in Lebanon and Yemen’s Houthi rebels, which obviously alienate the West and fly in the face of its interests. Regardless, the US said the election would not lead to a policy change to Iran, pointing out that the turnout was the lowest ever seen at a presidential election in the country, and even going as far to say “the elections in Iran were not free and fair. As a result, a significant number of Iranians chose not to participate at all.”

Ultimately, the dynamics of the Iranian political system is that the President is there to implement state policy outlined by the country’s Supreme Leader, who wields ultimate authority. Many are saying that Pezeshkian will be reformist in name only as he is simply there to shepherd through conservative acts. The US echoed a similar sentiment, saying “we have no expectation that these elections will lead to a fundamental change in Iran’s path or greater respect for the human rights of citizens. As the candidates themselves have said, Iran’s policy is determined by the leader.”

Syria keeping up appearances

On 15th of July, the Syrian regime of President Bashar al-Assad held elections for the Syrian parliament, the Syrian People’s Assembly (Majlis Al-Shaab). 250 seats were on offer in the unicameral chamber. Only 70% of the country took part in the election – the territory controlled by Assad. The assembly is a rubber-stamp parliament that lacks the power to initiate legislation, whilst the ruling Ba’ath Party’s electoral dominance remains certain.

The country remains almost irreparably divided following 13 years of civil war, albeit a 2020 ceasefire in Idlib has reduced the intensity of fighting. The Assad regime, with Russia’s support, has retaken large portions of formerly-held rebel territory. However, significant areas of the north are still under the control of the opposition, the most prominent of which are the Kurdish-led Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF) in the northeast, the Turkish-backed Syrian National Army (SNA) along parts of the Turkish border, and the Islamist group Hayat Tahrir al-Sham (HTS) in the northwest around Idlib.

In this time, Syria has continued to hold parliament, presidential, and local elections. Primarily managed by the regime’s Higher Judicial Committee for Elections (HJCE), they have been widely criticised for their lack of credibility. For example, Assad won re-election in 2021 with 95% of the vote. Turnout has been low – hitting 33% in the 2020 parliamentary elections, a fall from 57% in 2016. Opposition groups and their respective civilian administrative bodies have stated they intend to prepare separate electoral processes. The Kurdish SDF-connected Higher Electoral Commission of the Autonomous Administration of North and East Syria is preparing for municipal council elections, while in Idlib, the newly established HTS-linked Higher Elections Committee is planning for elections to the General Shura Council, the Islamist group’s civilian legislative body.

Since 2012, Syria has been ‘multi-party’, however power dynamics remain largely unchanged. According to Syrian opposition newspapers, there is an implicit understanding in the regime that around 183 parliamentary seats (secured by the coalition in 2020) out of 250 are reserved for the National Progressive Front (NPF), a left-wing coalition which includes Assad’s Ba’ath Party (166 seats) and several smaller pro-government parties (17 seats). Independents fill out the remaining 67 seats.

Candidate registration is marked by stringent controls to ensure loyalty. For this year’s election, around 12,000 hopefuls registered to run for election, with 9,194 approved during the candidate selection process, vetted by both General Intelligence and the HJCE. This is part of a historical pattern where both partisan and Independent candidates face scrutiny to pass the filter of alignment with regime interests, limiting genuine opposition representation. Another quirk of the system is that 127 seats are reserved for ‘workers’ and ‘farmers’, reflecting the Ba’ath Party’s historical socialist origins. However, the terms ‘worker’ and ‘farmer’ are poorly defined – some argue that these seats often go to regime allies with loose ties to these groups. There is no youth nor gender quota and women’s representation has historically been low. For example, in the 2020 election, women secured only 10.4% of parliamentary seats. Just 6.9% of seats were won by candidates aged 40 or younger.

The vote took place as Syria’s economy continues to deteriorate after years of conflict, Western-led sanctions, the COVID-19 pandemic, and dwindling aid due to donor fatigue. The value of the country’s national currency against the dollar has reached new lows, sparking food and fuel inflation. The Government has also partially rolled back its subsidy program almost a year ago while at the same time doubling public sector and pension wages. Regardless, according to the results, 185 candidates from the Ba’ath Party and its allies won seats as expected, an increase from the 183 seats won by the coalition in 2020.

The elections are seen by international observers and many within the country of just being a formality to provide the illusion of choice. Overseas opposition groups in exile described the election as ‘absurd’, saying that it only represented ‘the ruling authority.’ Fadel Abdulghany of the Syrian Network for Human Rights (SNHR) said “the elections for the People’s Assembly of Syria are conducted in an environment ruled by despotism, wherein the Syrian people cannot choose freely. The members of the Assembly are effectively selected by the security apparatus. These are unlawful elections that only reflect and represent the will of the Syrian regime.”

As the civil war wages on, and the Assad regime tightens its grip after a period of instability, it seems certain that, in the short term, Syria is not transitioning to a democracy and the chasm that has opened up between rival factions across the country (not least that between Assad and the Syrian Interim Government) looks set to widen still.

July’s elections were therefore largely symbolic, riddled with corruption, and heavily favouring the regimes that set the rules of the vote. Many in the UK can complain about the intricacies of our general election or voting system, but refer them to this article – our elections and the integrity of our vote could be far, far worse.