Domestically, the United Kingdom has and continues to have its fair share of elections. Following disastrous results for the Conservatives across the country, from Birmingham to Basildon, Reddith to Rushmoor, the Prime Minister Rishi Sunak MP announced his intention soon after to call a general election for Thursday, 4th of July.

This general election is important domestically (and will certainly carry international ramifications), and College Green Group stands ready to offer its analysis throughout the campaign and after polling day. However, in May, a significant number of presidential and parliamentary elections also occurred across the globe and whilst (to some) these may not be as enticing to analyse, they are still greatly significant when considering regional stability and the trajectory of democracy in certain countries.

Chad pits a President and a Prime Minister

For example, in the central African nation of Chad, voters went to the polls for the first time since an April 2021 coup following the death of President Idriss Déby who had ruled since 1990. Since then, Chad has been ruled by a military junta headed by the former President’s son Mahamat Déby, who called a successful referendum for December 2023 that established a National Transitional Council with the intention of transitioning the country from military rule into civilian rule.

When the election was called on the 28th of February, social unrest erupted in the capital city, N’Djamena. The government, headed by Déby, accused his opponents in the Socialist Party without Borders (PSF) of orchestrating attacks on the Chadian intelligence agency, and attempting to assassinate the head of the Supreme Court, Samir Adam Annour. This allegation provided cover for the Government’s forces to lay siege to the PSF headquarters in an attack that saw almost a dozen, including the party’s leader (who is also a cousin of Déby), killed. This was condemned by the French authorities and the African Union as a politically-motivated assassination against the main opponent facing the President.

Following this, the Chadian Prime Minister Succès Masra, announced his intention to stand for election. After an extended period of exile during which Masra had an arrest warrant issued by the Déby government, the Prime Minister was approved by the Constitutional Court and he signed an agreement with the Government to return to the country. This allowed, for the first time in history, an incumbent Chadian president to face an incumbent prime minister for the presidency.

The campaign was marred by open public dissent into the integrity of the electoral process. The ‘We the People’ coalition demanded the postponement of the presidential election and the opening of an inclusive national dialogue. The opposition platform Wakit Tamma called for a boycott of the presidential election, criticising a “masquerade” whose results were known in advance. In an opinion poll of members of the Chadian public conducted by the Center for Development Studies and the Prevention of Extremism, 487 of the respondents (50.9%) said they did not believe in the credibility of Chad’s electoral authorities (the National Election Management Agency (ANGE) and the Constitutional Council) because they are under the control of supporters of Mahamat Déby – a figure who just 7% of respondents view as a ‘credible candidate’.

Masra unveiled what he called a “minimum package of dignity”, which included a five-year plan to generate 200,000 jobs, divided equally between the private and public sectors. His grassroots campaign also promised to deal with other urgent issues like access to electricity, water, and security for all. Several of his supporters had been arrested on charges of forgery and using false documents to obtain access to vote counts throughout the campaign. Many of Déby’s supporters boasted of his success in optimising the country’s defence and security, national reconciliation, and the organisation of referendums on a new constitution – portraying him as a reformer who will protect the country’s interests.

Following the vote, Masra claimed victory on Facebook calling on his supporters and security forces to oppose what he saw as an attempt to steal the election. Provisional results were released later that day, indicating a decisive victory for Déby, who garnered 61.3% of the vote, surpassing the required threshold of 50% to avoid a runoff. Masra only secured 18.5% of the vote. Masra formally appealed to the Constitutional Council to have the election annulled, saying that his party, Les Transformateurs, had amassed evidence of electoral fraud. He resigned as prime minister shortly after the results were declared and replaced by Déby’s former Chief of Protocol and Ambassador of Chad to China, Allamaye Halina – who the President refers to as his “big brother.”

This election cements the Déby family’s continued rule in Chad and the appointment of a loyalist prime minister ensures that no other politicians in the country has a large enough platform to stage either a coup to Déby’s rule, or challenge him at the next election. With local and legislative elections scheduled for Autumn 2024 (as part of the transition back to civilian rule), and Chad’s role as a crucial partner for the West in terms of counter-terrorism and oil production, it is doubtful that attention will wane from the country – President Déby holds the cards.

The African National Congress left reeling after historic loss

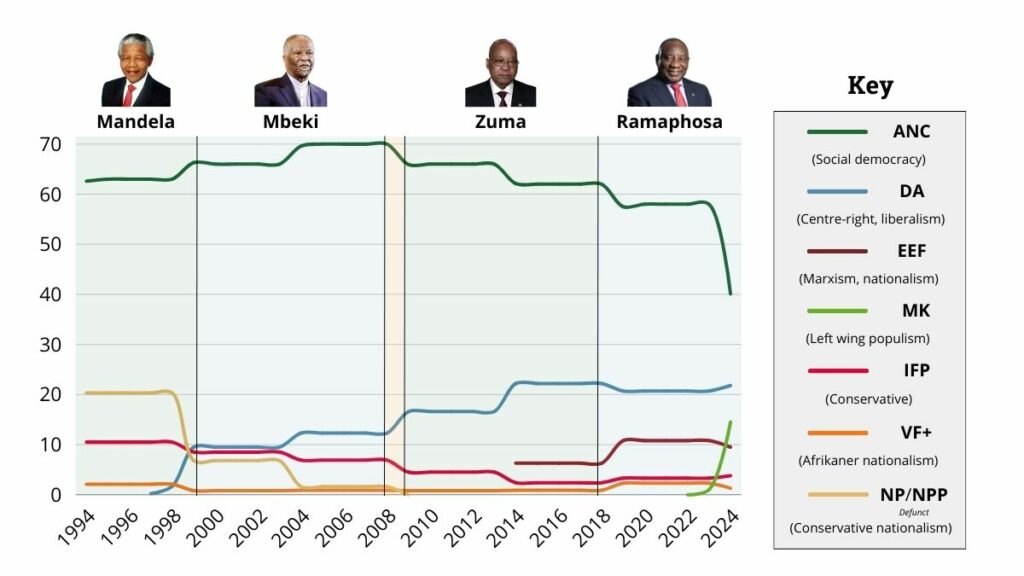

The African National Congress (ANC) swept to power in 1994 following the first national election in which people of all races could vote. The election marked the end of the apartheid system and produced President Nelson Mandela. Winning with over 62% of the vote and 252 seats in the 400 seat National Assembly, few would think that this would last. However, for the next two general elections until 2009 the ANC continued to gain seats and increase its share of the vote.

In 2009, the party suffered its first ever loss of parliamentary seats, and whilst its vote share held (at 65.9%), it still marked a decrease. This was the ANC’s turning point – at all subsequent general elections the party lost more seats, and more votes to other smaller parties, notably the Economic Freedom Fighters (EEF), a Marxist nationalist group.

In advance of this year’s election, many were watching as the ANC dropped in the polls, dipping below 50% for the first time in decades. Expectations that a hung parliament would be produced increased and warning shots were fired at the ANC in 2021 at the municipal elections in which its share of the vote fell 8.3% and where it lost control of 41 councils. The party lost critical support in Pretoria, Durban, and Johannesburg – former bastions of support, and in the latter the party had to enter a coalition with the EEF to retain control.

ANC leader, Cyril Ramaphosa’s woes did not end here. Former South African President Jacob Zuma announced he would leave the party in December 2023 accusing the party and Ramaphosa of serving as a “proxy for white monopoly capital.” He was also noted as calling the ANC “sellouts” and “Apartheid collaborators.” He also established his own political party, uMkhonto we Sizwe (MK), named after the apartheid-era military wing of the ANC. After less than a month, MK stood at 13% in the polls, taking a sledgehammer to the ANC’s support.

Soon after launching, the Electoral Commission barred Zuma from standing in the election, citing a previous criminal conviction. Eventually this decision was overturned, before the Constitutional Court ruled Zuma ineligible to stand once again.

The election campaign centred around corruption, land reform, healthcare, illegal immigration, foreign policy, and energy. In healthcare, Ramaphosa signed the National Health Insurance Bill into law, aiming to provide quality universal health coverage to all South Africans, but its implementation was met with opposition and scepticism. Among the concerns are that its execution will be undermined by widespread corruption and budget restraints, which see the country struggling to fund basic services. 80% of South Africans rely on strained state-run public health services while about 16% have access to private healthcare through medical aid plans. The move was accused of being a desperate attempt to shore up his party, with the Democratic Alliance (the chief opposition party) launching a legal challenge to the law.

In 2022, the Judicial Commission of Inquiry into Allegations of State Capture, known colloquially as the Zondo Commission completed its work and submitted its final report to Ramaphosa in June 2022. Costing almost R1 billion (£42,170,199), the ANC responded saying that “laws, institutions and practices are being put in place to reduce the potential for corruption of any sort and on any scale.” However, the Democratic Alliance alongside the MK accused the ANC of presiding over decades of sleaze and political crime.

One area that saw the ANC pressured from the left was on land reform. The ANC’s proposed amendment of Section 25 (that ‘No one may be deprived of property except in terms of law of general application, and no law may permit arbitrary deprivation of property’) of the constitution of South Africa failed in the National Assembly. The ANC maintained that expropriation without compensation was necessary, as did the EFF. Moves towards expropriation without compensation are largely framed as solutions to racial injustice. In fact, many members of pro-expropriation parties view the policy as fulfilling Nelson Mandela’s promise to return 30% of South Africa’s land to black people. The issue of racial justice becomes particularly salient when looking at disparities in agricultural production and environmental harms, with the majority of land in South Africa being owned by white people. Reports from the South African government indicate that whites own 72% of total farms of agricultural holdings, meaning that black South Africans are generally only responsible for between 5 and 10% of the country’s agricultural output. On this matter the ANC was pushed to the left by the EEF who had made the issue key to their policy platform – Julius Malema, leader of the party, asserted that “when we say economic freedom, we mean Black people own productive farms.”

These issues, alongside high unemployment, power cuts, violent crime, and crumbling infrastructure contributed to a haemorrhaging of support for the ANC. Come election day, the party won just 159 seats in the 400-member national assembly on a vote share of just over 40% – an unprecedented fall of over 17%. Mirroring the previous municipal elections, the ANC also lost its majority in Johannesburg and the capital, Pretoria.

The ANC insisted “if you come to us with a demand that Ramaphosa must step down as the president, that is not going to happen … It’s a no-go area. You come to us with that demand, forget it.” The ANC, as the largest party, has the first right to pursue coalition arrangements – some have suggested that the Democratic Alliance could be the preferred partner of the ANC, while others say the EEF could assuage the left wing flank within the party (an option being described as a ‘doomsday coalition’ by the Democratic Alliance).

Analyst Oscar van Heerden said that coalition negotiations are unlikely to be easy because the “Democratic Alliance has approached the ANC as the enemy over many, many years” saying it would “possibly give stability”, though be internally a deeply controversial decision. Ramaphosa knows he is likely on borrowed time, during which he needs to make a choice that will leave his party stinging – whether to concede to the far left, or give up on decades of principles and tack right. The 2024 election could be the last the ANC contests should he fail to navigate the storm he is about to face without pragmatism.

Catalonia votes for calm over constitutional crisis

Catalonia has endured a troubled recent history. Just six years ago, the autonomous region of Spain was at the centre of a constitutional crisis. It started after the law intending to allow the 2017 Catalan independence referendum was denounced by the Spanish government under Prime Minister Mariano Rajoy and subsequently suspended by the Constitutional Court until it ruled on the issue. Former Catalan Prime Minister, Carles Puigdemont announced that neither central Spanish authorities nor the courts would halt their plans and that it intended to hold the vote anyway, sparking a legal backlash that quickly spread from the Spanish and Catalan governments to Catalan municipalities.

The referendum was eventually held, albeit without meeting minimum standards for elections and amid low turnout. Spanish police were sent in to seize ballot boxes in unprecedented scenes for an EU member state and direct rule was invoked over Catalonia. Puigdemont encouraged the Catalonian Parliament to vote in a secret ballot to unilaterally declare independence from Spain, whilst Spain issued a warrant for his arrest. Shortly after, he fled to Belgium.

It would seem inconceivable that the man at the centre of this crisis would be allowed anywhere near elected office again – but Puigdemont once again defied convention. The former president of the Catalan government remains subject to a warrant in Spain for disobedience and misappropriation of public funds, for the October 2017 secession attempt. As he waits for the final vote on the amnesty law – granted by Pedro Sanchez’s minority Spanish government in exchange for support for his vote of investiture for the seven MPs.

This election mattered for the balance of power between the two main forces contending to dominate Catalonia’s pro-independence camp, divided between centre-left and centre-right. But it will also be key for the strength of Spain’s Socialist-led government, just days after Prime Minister Pedro Sánchez announced that he had decided not to resign. This loomed over the Catalan electoral campaign. The pro-independence parties denounced Sánchez for holding double standards — and looking away when they were themselves targeted by harsher smear campaigns. The fall of Sánchez’s government might have opened the way to new Spanish elections — and that a new, right-wing government in Madrid, with a more bellicose line on Catalonia, could easily have come to power.

Puigdemont ran again for President as the candidate of Junts (Together), a centre-right, pro-independence party. This political space has taken many different names and incorporated many new members over the last decade. He was assessed as Junts’s best hope to reverse the results of the 2021 election. Back then, the centre-left wing of the pro-independence camp, Esquerra Republicana de Catalunya (ERC), gained more votes and seats than Junts. After the 2021 vote, ERC regained the presidency of Catalonia for the first time since the Spanish Civil War, under Pere Aragonès. Aragonès initially headed a coalition government with Junts that was only three seats short of a majority. After Junts quit in October 2022 — arguing that ERC was not committed enough to their joint pro-independence agenda — Aragonès had a very weak government, counting on the support of just thirty-three MPs — under a quarter of the total.

The Junts campaign has been highly personalised around Puigdemont who has promised to return to Catalonia after the elections. That is not a new promise, but one he also made before both the 2017 Catalan elections and 2019 European elections. The former president, however, retains a loyal support base, especially in the interior of Catalonia, away from the capital, Barcelona.

The Catalan wing of the Partido Socialista, led by Salvador Illa, Spain’s former health minister, has been running a centrist campaign. Illa has sought the support of the main unions but also been attentive to the demands of the employers’ associations, who have been courting him for years. In the negotiations for the ERC-led government’s 2023 budget, which the Partido Socialista ultimately supported, Illa obtained several concessions long demanded by employer groups — among them a commitment to ‘modernise’ Barcelona’s airport.

For Sánchez’s and Illa’s Partido Socialista, finishing first was essential to have one of their own as president of Catalonia. In the election, the party gained nine seats but forming a government will be very complicated. Even in their best-case scenario, the Partido Socialista would need an agreement with Puigdemont’s Junts, which has rejected the idea, or else the centre-left, pro-independence ERC, who may face difficulty accepting a secondary role after having led Catalonia these past three years. Junts gained three seats and increased its vote share by 1.5% – perhaps a disappointing showing for the party.

Analysts believe that the dent in the secessionist parties’ support likely represents the electoral finish line for the “procés”. That’s a term (meaning process) used by Catalans to define the political turbulence that from 2012 onwards pivoted on widespread, but by no means universal, demands for a regional referendum on Catalan independence, which took place in 2017. Germa Capdevila, Catalan political analyst, cited rising public disappointment with Catalonia’s current entourage of pro-independence politicians as a reason for the lacklustre performance, and also for the historically low voter turnout. Some people have voted for calm after seven years of constitutional crises and civil turmoil.

Support for independence has dropped from 49% in 2017 to 42%, says the Catalan government’s statistics institute, and other issues, such as the region’s drought and housing crisis, have driven the modern political debate. Whilst the Partido Socialista has won the most seats it will not be easy for Illa to form a government, given he is likely to need the support of pro-independence ERC and the far-left Comuns Sumar alliance. Puigdemont called for ERC not to be part of a coalition that included the unionist Partido Socialista. He suggested the two main pro-independence parties should try to form an administration, as they had done in the past before their relationship broke down. Whilst voters chose calm over chaos, they may still be forced to endure months of coalition wrangling to form a government that might not even last the summer.

Not only do politicos in the UK have the general election to look forward to, but they also have European Union parliamentary election results to pore over. The sentiment within individual member states will be revealed, whilst crucial data to gauge the support of the far-right in Finland, France, Germany, and Greece will be outlined. Iran, reeling from the sudden death of President Raisi, will hold impromptu presidential elections in which 21 candidates including former President Ahmadinejad have declared their candidacies. Finally, Bulgaria will vote in its parliamentary elections in which eyes will be focused on the performance of ‘Revival’, a far right party that might hold the balance of power following the vote. Plenty to be excited about – and we’re not even half way through the year!