September arrived, and with it some mixed weather – from glorious sun that gave hope that Summer was yet to remain for another few weeks, to dismal rain and storms confirming that Autumn had arrived. Sticking with this analogy, elections can be weathervanes for the sentiments within a country or even a continent.

We saw in the German state elections through the historic results for the Alternative für Deutschland (AfD) and the new left-wing Sahra Wagenknecht Alliance (BSW), that the country is drifting away from the centre and being pulled towards the ideological fringes.

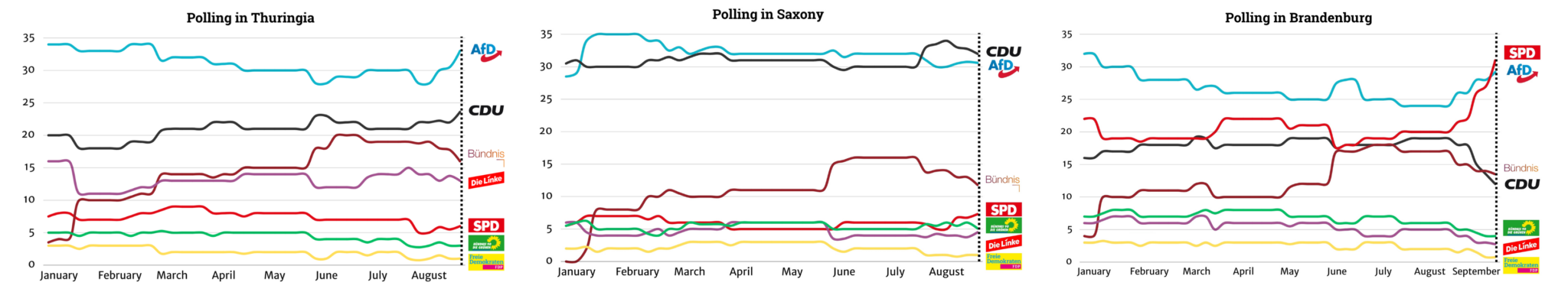

The AfD has been riding a populist wave across Germany for over a decade, and were a federal election held tomorrow it would likely be returned as the second largest party in the Bundestag. However, as recent state elections indicate, only in what was formerly East Germany have they shown their true winning potential. In elections in Thuringia, Saxony, and Brandenburg, the AfD rose 6.0% to secure 30.8% of the vote across the three states. This figure may not seem impressive in isolation, however considering the next nearest competition was the Christian Democrats (CDU) who secured 22.5%, this is a worrying sign for many in German politics.

A new development from the other side of the political spectrum came with the BSW. It advocates for an interesting political ideology of left-leaning economic policies and anti-immigration rhetoric. Some political scientists argue that it has borrowed nationalist policies from the AfD, whilst leaning on its unorthodox style of populism to appeal to apathetic voters. Founded from a split with the ‘Left’ Party (Die Linke), its leader Sahra Wagenknecht said that her new political vehicle would not enter into coalitions with centre-right and left parties as easily as Die Linke. She has been accused of leaning on pro-Russia talking points in reference to the war in Ukraine, and of promoting a programme that is intentionally vague on climate, education, and economic policy. The BSW’s success in recent state elections in former East Germany may owe much to nostalgia amongst some voters for the old 1949 – 1990 republic. Professor Matt Qvortrup of Coventry University contends that “the BSW’s promises of strong social security rooted in left-wing policies appeal to voters who had felt more protected by the welfare state before reunification.”

Across these three state elections, the BSW secured 13.7% of the vote, beating the German Greens and Die Linke, but coming just one percent short from beating the Social Democrats (SPD). For a party founded in January on a platform of Euroscepticism, left-wing nationalism, and anti-NATO sentiment, its success is remarkable. Likewise, its impact on German politics looks set to also take effect. The ruling SPD is already whispering about allying with the BSW to keep the AfD from the levers of power, and the CDU in Saxony is also musing about what cooperation could take place with the BSW to keep the AfD from state government. Were the SPD to combine its seats in the Brandenburg State Parliament with the BSW, it would achieve a majority, it’s a similar story in Saxony with the CDU. However, would a party that has built its image and reputation of being proudly anti-establishment wish to enter into an arrangement with Germany’s ultimate establishment parties?

Algeria’s military returns its man to power

Algeria conducted its presidential election in early September under a cloud of dissent. President Abdelmadjid Tebboune, first elected in 2019 with 58.1% of the vote, has recently introduced new legislation that has been accused of attempting to stifle any vote. The country’s pro-military establishment had strongly supported Tebboune from the beginning and was seen by some as instrumental in the new legislation passing.

The new law which moved the vote from December to September means the election took place in significantly hotter weather than otherwise. Critics contend the motive was to reduce turnout in Tebboune’s favour. In the 2019 presidential election, only 39.8% of the country cast ballots, whilst the 2021 legislative elections saw just 30% turnout – however it is worth noting that these can largely be attributed to the Hirak pro-democracy protests that toppled Tebboune’s predecessor, Abdelaziz Bouteflika.

The election campaign was primarily fought on economic lines. Over half of the Algerian population are young people, so messaging focused on creating more, better paying jobs, and offering more support to those in one of the country’s largest sectors – natural gas. Tebboune, running on the accomplishments of his first term, fought on a pro-business, pro-export, yet authoritarian platform designed to quell any industrial or social unrest. This stands in contrast to his challengers, Abdelaali Hassani Cherif and Youcef Aouchiche, who both pledged a liberalisation of the country. Aouchiche has promised to “release prisoners of conscience through an amnesty and to review unjust laws”, including on media and terrorism.

However, despite these calls, Tebboune secured re-election with 84.3% of the vote. Cherif accused polling station officials of inflating results and not counting all votes. Whilst turnout increased by over 6%, younger Algerians largely did not turn out to vote.

Tebboune’s re-election means Algeria will likely continue with a governing programme that has been characterised by lavish social spending based on increased energy revenues after he came into office in 2019 following a period of lower oil prices. His election comes after he pledged to raise unemployment benefits, pensions and public housing programmes, all of which he increased during his first term as president.

This election is not to be treated as a particularly accurate reflection of the sentiment of the Algerian population. The country is classified as ‘not free’ by think tank ‘Freedom House’ and outside observers have not been allowed into the country to monitor the poll and according to Amnesty International, Algerian authorities under Tebboune “have maintained their repression of civic space” and “a zero-tolerance approach to dissenting opinions”. The Algerian military looks set to continue its firm grasp on society and politics – this comes at a crucial time for the country as Russia and China look to expand their operations on the continent.

Gaza backlash sees Islamists surge in Jordan

Those living on Jordan’s western flank can see smoke from nearby Gaza. It is no surprise that this issue was a prominent part in the country’s general election to its House of Representatives. Though King Abdullah II is the ultimate authority, the House plays a key role in terms of introducing and passing legislation, but also legitimising the Kingdom’s political system during times of tension in the region and at home such as now.

Jordan’s Independent Elections Commission (IEC) made some ripples when it called for elections to take place this month (with the King’s assent), amidst the war taking place mere miles away. The 2001 election, which coincided with the second intifada, was initially postponed and held instead in 2003, the same year that the US-led war on Iraq began. Some are saying this timing was deliberately chosen to benefit Islamist parties who would benefit from public outrage against Israel. The data supports this with a poll conducted by The Washington Institute for Near East Policy in December 2023 finding 85% of Jordanians holding a favourable opinion of Hamas, a near doubling of support since 2020 when the last poll found this figure at 44%. This comes at a time when Jordanians favour increasing the role of religion in politics with a 2023 Arab Barometer poll finding 49% supporting such a proposal.

The chief Islamist Party, the Islamic Action Front (IAF), the political arm of the Jordanian Muslim Brotherhood, has been opposed by the Government for decades. It conflicts with the King’s socio-political agenda characterised by moderation and warmer ties with the West and Israel. This is clearly a concern as the Government introduced a new election law in February that would curtail the success of the IAF, regardless of how popular they were. This was a similar approach by the Government to their 1989 curtailing of the Muslim Brotherhood that also sought to lessen the influence of tribal MPs in the chamber.

Following the ballot, the IAF managed to win the most seats in the House of Representatives, securing 31 of 138 and tripling its representation. This marks the largest cohort of Islamist MPs since they gained 22 of 80 seats in 1989. “The elections reflect the desire for change and those who voted were not necessarily all Islamists but wanting change and had become fed up with the old ways,” said Murad al-Adailah, the head of the Muslim Brotherhood. Al-Adailah also said that the success of the party was a “popular referendum” that backs their platform of support for the Palestinian group Hamas, their ideological allies, and their demand to scrap the country’s peace treaty with Israel.

Some Islamists and political analysts believe that Jordanian authorities deliberately kept away from intervening in the electoral process so their success would send a message to the USA and the West in general that allowing Israel to commit violence and aggression will generate radical Islamist currents. However, others contend that voting for Islamists is a consequence of declining trust in the government. This gap has been widening for years since Jordanians felt that successive governments failed to find adequate solutions to economic issues that impact their living standards, decrease poverty (now at 35%), and reduce unemployment (at 21.4%).

The IAF’s success in a country characterised by its pragmatic approach to Israel and Palestine is an alarming warning that the population of one of Israel’s neighbours is through with towing the Government line, regardless of how popular the King is.

Austria lurches to the right and to Russia

Similar to Germany, Austria also had its moment to stun, veering to the right in a watershed election. Winning 29% of the vote, the Freedom Party (FPÖ) pushed the centre-right Austrian People’s Party (ÖVP) down to 26%, and the Social Democrats to its worst ever result. With 80% of voters turning out to cast ballots, like Germany, the results are a worrying sign for European solidarity. Not only has the party expressed pro-Russia sentiment, but FPÖ leaders regard Hungarian Prime Minister Viktor Orbán, who has systematically dismantled democratic freedoms in his country, as a model and have promised to follow his lead.

Founded in the 1950s by former members of the German SS, the party pledged to create a ‘Fortress Austria’ to ‘keep out migrants’ with the party’s leader, Herbert Kickl promising voters that if they handed him the win, he would serve as their Volkskanzler, or ‘people’s chancellor,’ a term once used by Adolf Hitler. Whilst it denies its past, the party recently displayed its affection for the Third Reich at a recent funeral for a long-serving FPÖ politician, where mourners, including a number of FPÖ leaders past and present sang an SS anthem.

Whilst it topped the poll, the business of coalition now begins. To become Chancellor, Kickl must be nominated by the country’s President, Alexander Van der Bellen. The President is seen as unlikely to do so, however it would be difficult to ignore the FPÖ’s performance. That means the party has a fair chance of building an alliance with the centre-right, which has ruled out working with Kickl, if the FPÖ fields a different candidate for Chancellor. Some contend that a three way coalition between the ÖVP, the Social Democrats, and the liberal NEOS is more likely – but could quickly crumble owing to the vast ideological divide between the three.

How did the FPÖ do so well? It capitalised on fears around migration, asylum and crime heightened by the August cancellation of three Taylor Swift concerts in Vienna over an alleged Islamist terror plot. Mounting inflation, tepid economic growth and lingering resentment over strict government measures during Covid-19 dovetailed into a huge leap in support for the FPÖ since the last election in 2019.

At his final campaign rally in Vienna, Kickl railing against anti-Russia EU sanctions, “the snobs, headteachers and know-it-alls”, climate activists and “drag queens in schools and the early sexualisation of our children”. He hailed a proposed constitutional amendment declaring the existence of only two genders. However, the largest applause line was for his call for “remigration”, or forced deportation of people “who think they don’t have to play by the rules” of Austrian society.

Negotiations on who will be Chancellor look set to take weeks, yet regardless of the outcome the ÖVP seem poised to retain power either in an alliance with the FPÖ (though without Kickl), or an unwieldy three-way coalition like Germany. With federal elections taking place in Germany next year and its equivalent of the FPÖ in second place, this could be an important case study for how to navigate this complicated challenge and avert returning to the ideologies of the 1930s.

As October commences, we have plenty of exciting elections to watch in Botswana, Mozambique, and Tunisia, some important assembly elections across Canada that could shed some light on how Prime Minister Trudeau is faring with the electorate, and in Moldova – where a pro-West, pro-EU president is locked in a close fight against a pro-Russia contender in a highly consequential vote.