Mass protests erupted after a young woman was brutally murdered by Iran’s so-called ‘morality police’ for incorrectly wearing her hijab. Mahsa Amini has now become a brave icon for the fight of Iranian women against oppression. However, this is not all she ought to be remembered for. Jina Amini, a Kurd who was forced to change her name due to government restrictions on ethnic names was a symbol of the undeniable exploitation and ethnic cleansing experienced by the stateless nation of Kurdistan at the hands of Iran’s theocratic regime.

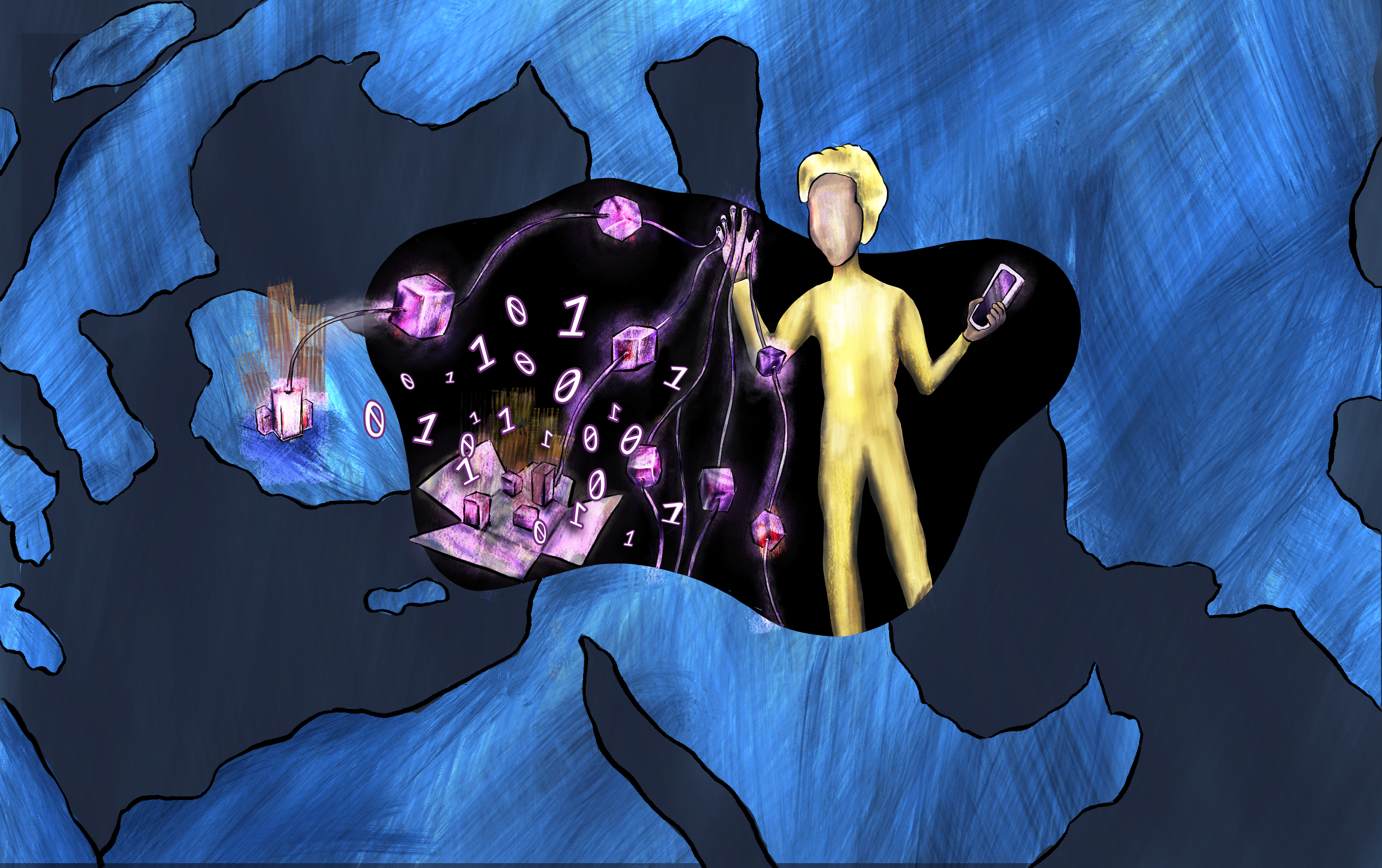

At least 10 million people, including Kurds, are considered stateless by the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR). The consequence is a forgotten crisis of marginalisation and political persecution of a group of individuals with insufficient evidence of their existence as human beings. Faced with exclusion from basic human rights, such as education and free movement, stateless populations continue to suffer as their burden is passed down to new generations, leading to the formation of a vicious cycle of abuse with no signs of justice being imminent. However, recent developments in blockchain technology have shown its potential to be used as a tool to form the basis of legal identity of a stateless person, thus providing some much-needed optimism to these silent sufferers in an unhearing world.

Could blockchain technology be a beacon of hope?

Blockchain technology is primarily known for its association with cryptocurrencies. It is a decentralised, distributed database of information that is stored on many different computers worldwide in structures known as blocks. This data cannot be changed and is independently verified on numerous devices, making it highly secure and trustworthy. The potential positive impacts of this disruptive technology are enormous. Recently, blockchain has been lauded as a key innovation that can be used to solve critical social issues, such as empowering those without a legal identity.

One challenge often faced by stateless individuals is the requirement of proper documentation or permanent address to access financial services. Studies have repeatedly shown that this makes them more vulnerable to exploitation; these individuals often do not have a bank account for employers to pay salaries into, which means that they are often forced to work in unacceptable conditions for less than minimum wage, receiving their pay in cash with no official record of their hardship. The World Food Programme (WFP), a UN organisation, has been exploring the practical applications of the blockchain in creating novel solutions to this issue of financial inclusion through the creation of the Building Blocks project in 2016. The mechanism, powered by blockchain technology, allows individuals to receive WFP monetary aid directly into their digital accounts. Biometric information stored in the UN database is linked to a person’s profile so they can spend these TFP funds through iris scanners at shops instead of needing a bank card, thus providing them an alternative pathway to access essential services. The record of transactions made using the online system is stored on the blockchain, and a detailed digital log is created, which can then be used as a blueprint for proof of a person’s existence and identity.

The potential for self-sovereignty

The accumulation of data across the shared blockchain network, such as biometrics and a history of transactions, provides irrefutable evidence of the existence of an individual, therefore having the potential to be used to make up part of their legal identity. According to a report from Reuters this vision is being brought to reality through the joint effort of Accenture Plc and Microsoft Corp; their project involves using blockchain technology to deliver a form of digital identification that can be accessed through any electronic device. This technology could be immensely useful for the substantial proportion of stateless people who do not have access to a secure home to store their paper documents, but do have one universal item – a mobile phone. Currently, only 23% of the Somali population has sufficient proof of their legal identity, while 90 percent own a smartphone. With access to this innovative technology, Somalis could use any device with internet access, whether their own or one that they borrowed, to take control of their identity.

The concept of self-sovereignty is crucially important in safeguarding the welfare of stateless individuals. The World Identity Network carried out an investigation into common practices by human traffickers and found that taking away paper identification documents is a tactic that is often used to hijack the victim’s identity, thus making it easier to coerce this now stateless person into dangerous situations. The use of blockchain identification methods would solve this problem. The possibility of accessing documents on a digital system powered by blockchain means that no one would be able to seize complete control of another person’s identity as it would be securely linked to their biometric information.

However, this is not the only external threat to the control of the proof of a person’s existence. Under the current status quo, governments have an unjust monopoly as the sole custodians of the identification of their citizens. They have the power to strip a person of citizenship, often with insufficient checks and balances, thus violating their right to a legal identity. This has been abused by governments and used as a tool to commit further rights violations; for example, the Rohingya community had their citizenship in Myanmar gradually taken away in a broader attempt by the ruling military junta to pursue a policy of ethnic cleansing. The response of the United Nations to the critics has been criticised as inadequate in fulfilling its mandate in accordance with the principles of human rights. The technological solution of blockchain suggests that relying on the inter-state political system to resolve this issue is an unwise and potentially fruitless endeavour. By empowering self-sovereignty, another benefit of the blockchain is that, as a consequence, it decouples citizenship and legal identity. This effectively breaks up the monopoly that governments possess over a person’s existence and reduces the state’s corrupting power by taking away a crucial tool of coercion.

Indeed, the possibility of a system of self-governance seems highly attractive to people whose proof of existence has been unjustly monopolised by the state. It would empower stateless Kurdish minorities in Iran to have the ability to collectively unite and stand up against the tyranny imposed upon them by the theocratic regime. Rohingya communities in Myanmar would have the power to resist the genocide and persecution that they have suffered for decades at the hands of the military dictatorship. Blockchain technology can provide Kurds, Rohingyas, and 10 million other stateless people with a light at the end of the tunnel amid their seemingly endless hardship.